Empire and colonialism

Filter stories by this topic-

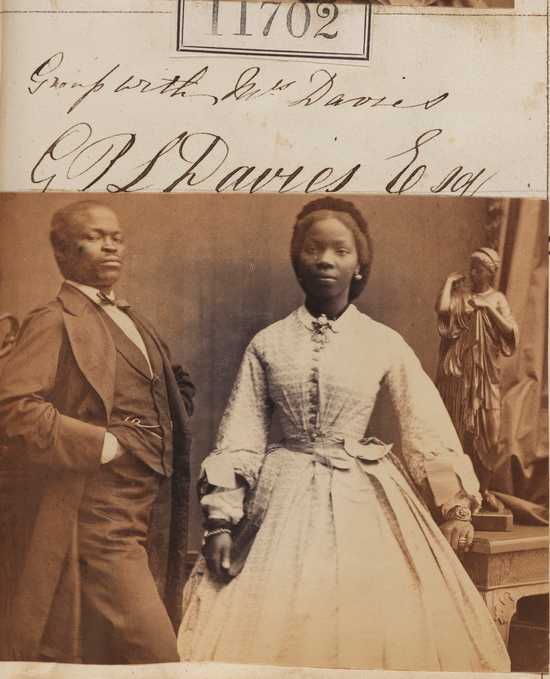

Sarah Forbes Bonetta: from captive to British celebrity

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Story

StorySarah Forbes Bonetta: from captive to British celebrity

-

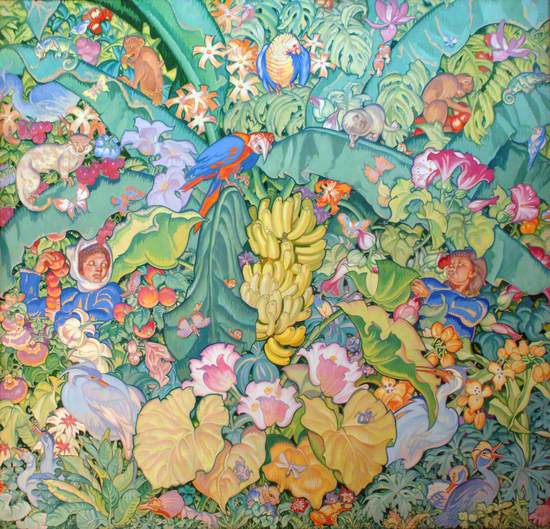

The Brangwyn Panels: painting the tangled abundance of the British Empire

© the artist's estate / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: City & County of Swansea: Glynn Vivian Art Gallery Collection

Story

StoryThe Brangwyn Panels: painting the tangled abundance of the British Empire

-

Rediscovering Black Portraiture: unshackled, reimagined, seen

'James Hunter (Black Draftee)' by Alice Neel. re-creation by Peter Brathwaite (with photographic partner Sam Baldock). © Peter Brathwaite. Image credit: Peter Brathwaite

Story

StoryRediscovering Black Portraiture: unshackled, reimagined, seen

-

On representing Mary Seacole: a Jamaican-Scottish war heroine

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Story

StoryOn representing Mary Seacole: a Jamaican-Scottish war heroine

LGBTQ+ subjects

Filter stories by this topic-

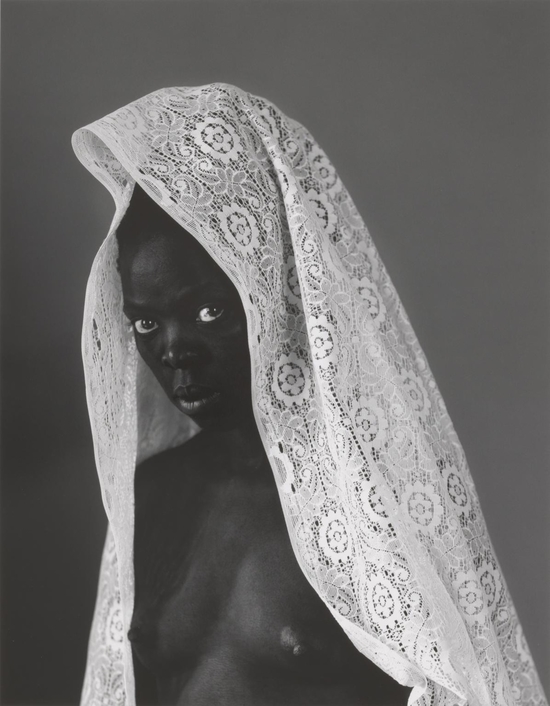

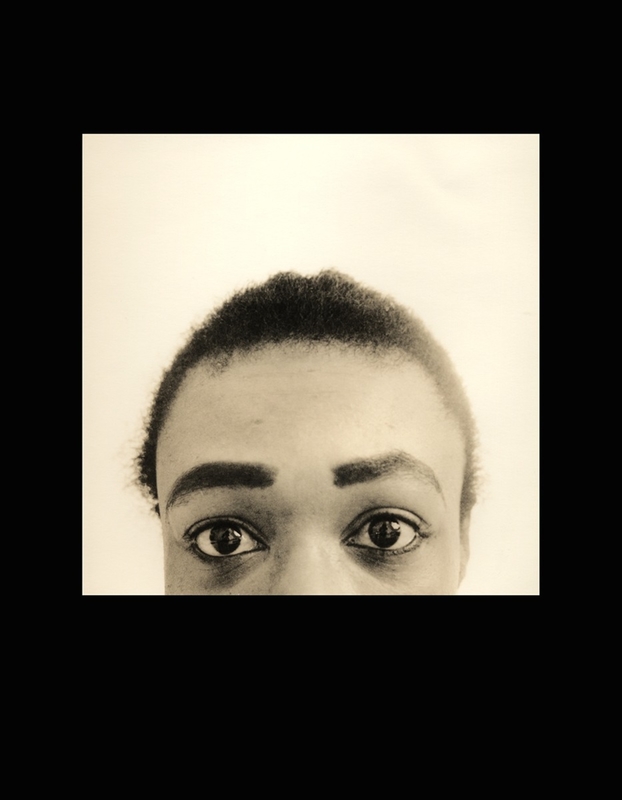

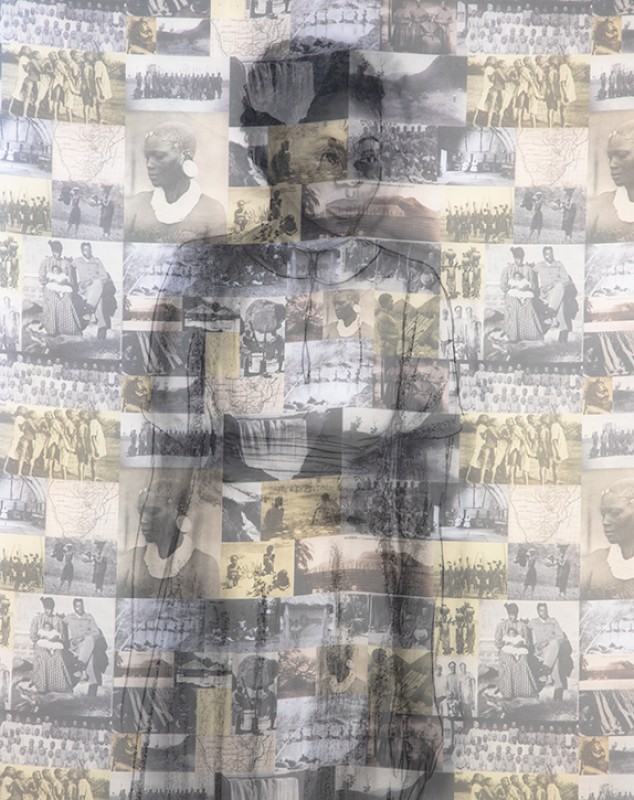

Zanele Muholi: championing black and queer visual narratives

© the artist. Image credit: Tate

Story

StoryZanele Muholi: championing black and queer visual narratives

-

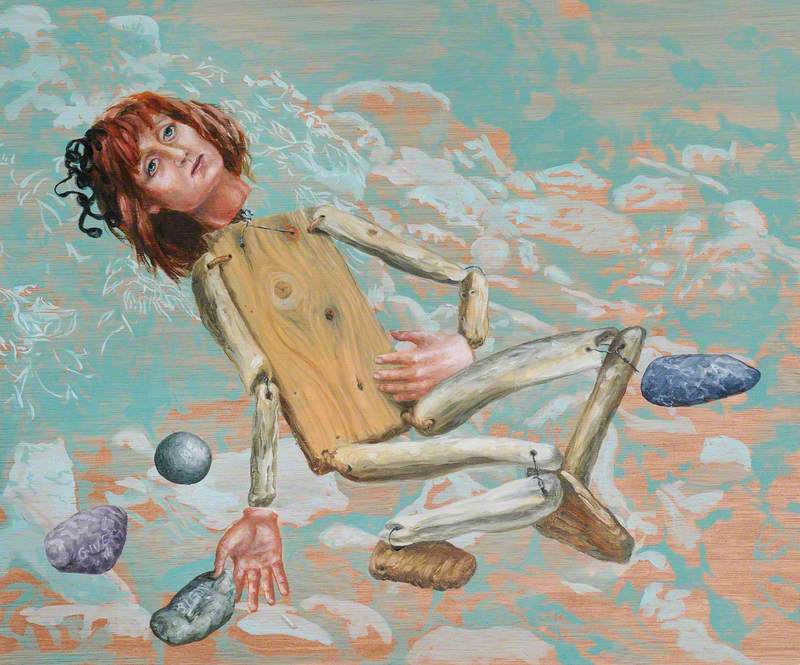

Derek Jarman's garden: a heart of creativity

© the artist. Image credit: The Priseman Seabrook Collections

Story

StoryDerek Jarman's garden: a heart of creativity

-

Saint Sebastian as a gay icon

Image credit: Bridgeman Images

Story

StorySaint Sebastian as a gay icon

-

'Here comes the goose!': Elizabeth Siddal's strangely sapphic sentinels

Image credit: Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Story

Story'Here comes the goose!': Elizabeth Siddal's strangely sapphic sentinels

Feature

View all 650-

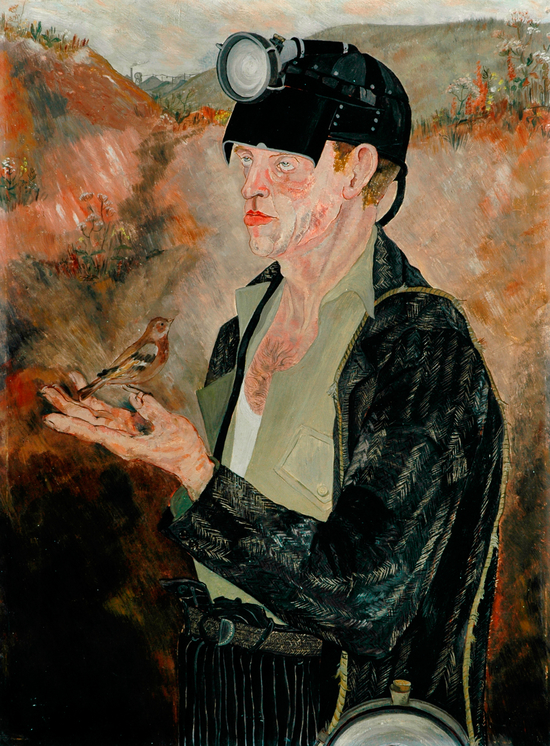

From the earth comes light: women artists and British mining 1 May 2024, Jennifer Jasmine White

From the earth comes light: women artists and British mining 1 May 2024, Jennifer Jasmine White -

Scottish independence: Scotland's national identity in art before the Act of Union 30 April 2024, Fern Insh

Scottish independence: Scotland's national identity in art before the Act of Union 30 April 2024, Fern Insh -

The power of blue: humanity, spirituality and divinity 26 April 2024, Elle Anderton

The power of blue: humanity, spirituality and divinity 26 April 2024, Elle Anderton -

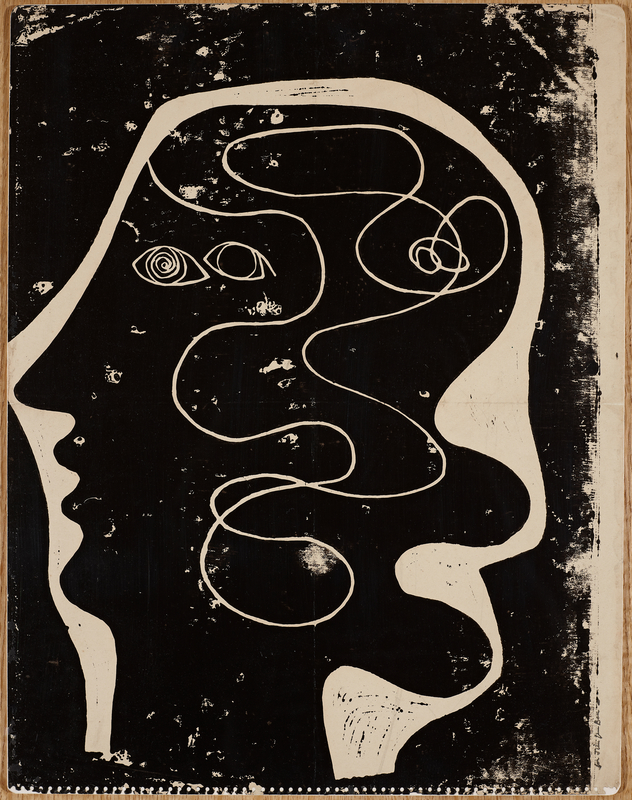

Five twentieth-century artists who reimagined the human figure through drawing 25 April 2024, JoAnna Novak

Five twentieth-century artists who reimagined the human figure through drawing 25 April 2024, JoAnna Novak -

Beyond the pale: blushing and whiteness in eighteenth-century portraits of women 24 April 2024, Janet Couloute

Beyond the pale: blushing and whiteness in eighteenth-century portraits of women 24 April 2024, Janet Couloute -

Concrete Canvas: how is Chelmsford's street art festival put together? 23 April 2024, Candy Joyce

Concrete Canvas: how is Chelmsford's street art festival put together? 23 April 2024, Candy Joyce -

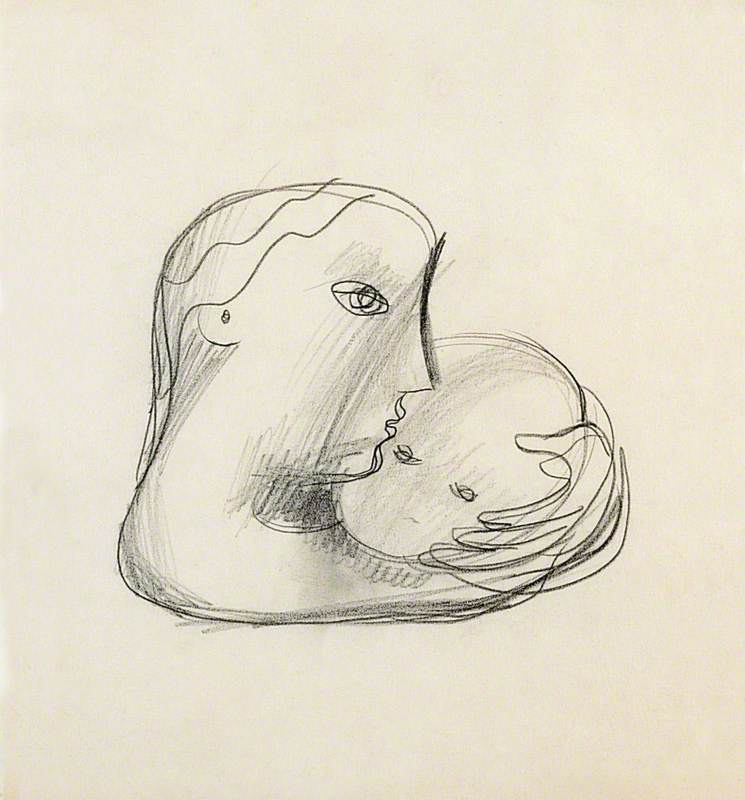

Lines of connection: drawings of mother and child 22 April 2024, Alice Read

Lines of connection: drawings of mother and child 22 April 2024, Alice Read -

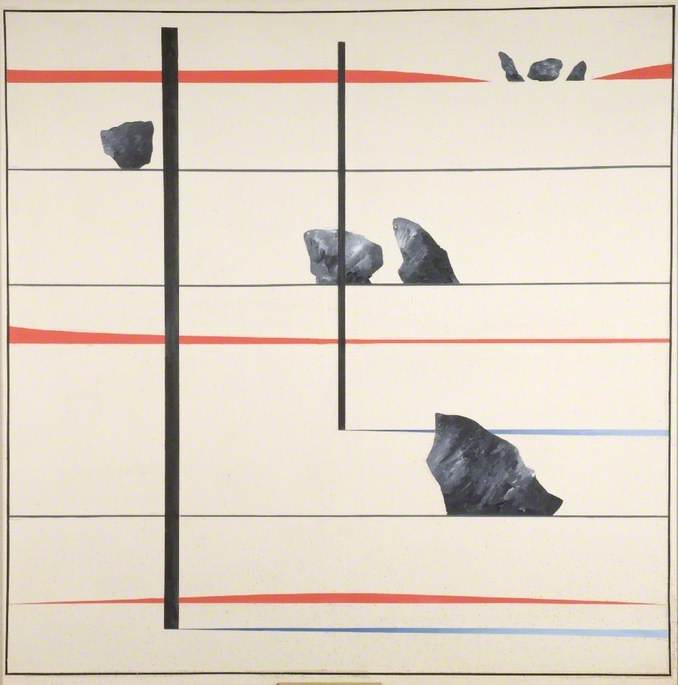

Sites of ancient power: the enduring magic of standing stones in British art 19 April 2024, Eleanor Affleck

Sites of ancient power: the enduring magic of standing stones in British art 19 April 2024, Eleanor Affleck - View all 650

Artist in focus

View all 483-

Moonlight and northern towns: the enduring appeal of John Atkinson Grimshaw 7 May 2024, Adam Wattam

Moonlight and northern towns: the enduring appeal of John Atkinson Grimshaw 7 May 2024, Adam Wattam -

Paula Rego's pastel world 3 May 2024, Alice Blow

Paula Rego's pastel world 3 May 2024, Alice Blow -

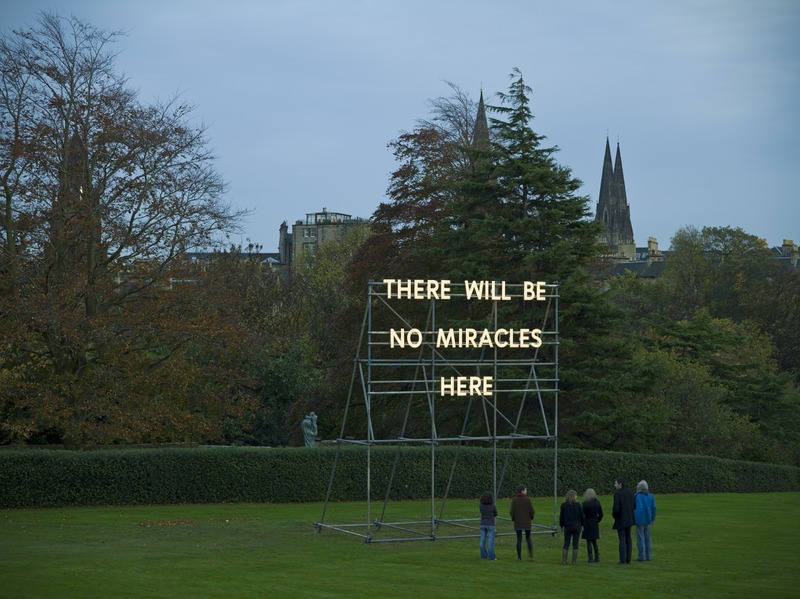

Nathan Coley: profound ambiguity 2 May 2024, Neil Lebeter

Nathan Coley: profound ambiguity 2 May 2024, Neil Lebeter -

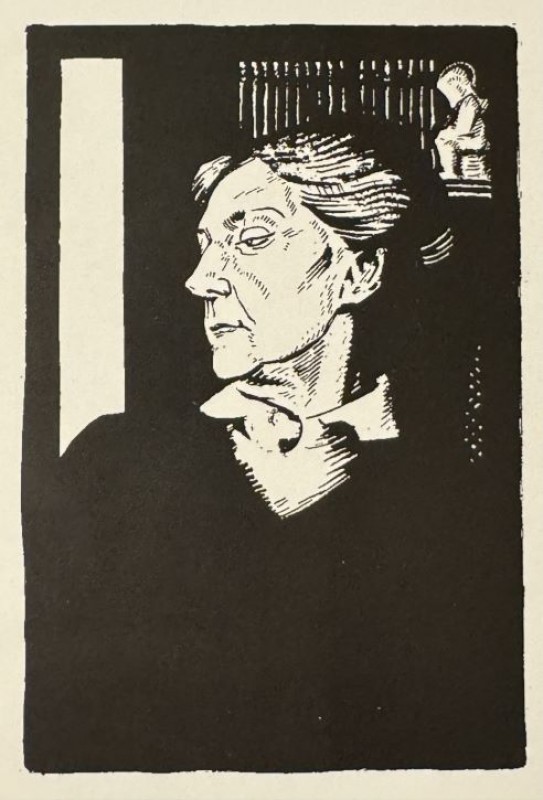

Sophia Rosamond Praeger: Irish artist and campaigner for women's rights 17 April 2024, Joseph McBrinn

Sophia Rosamond Praeger: Irish artist and campaigner for women's rights 17 April 2024, Joseph McBrinn -

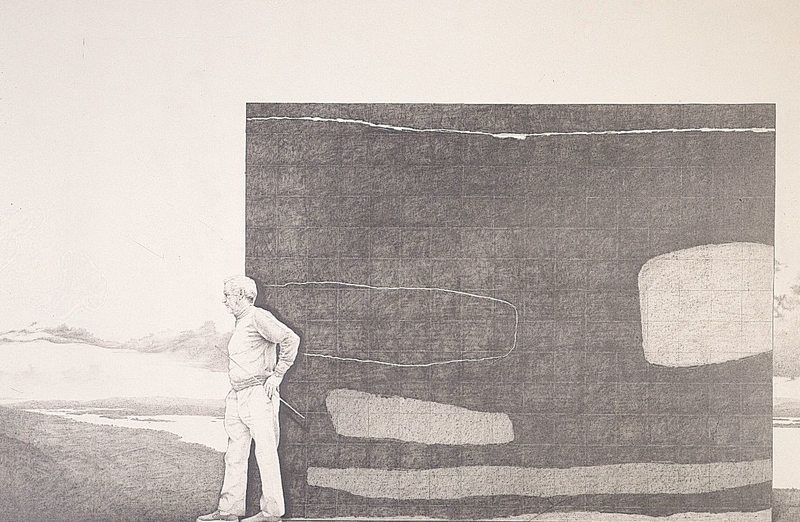

William Scott in Northern Ireland: an austere world and the things of life 16 April 2024, Claire Dalton

William Scott in Northern Ireland: an austere world and the things of life 16 April 2024, Claire Dalton -

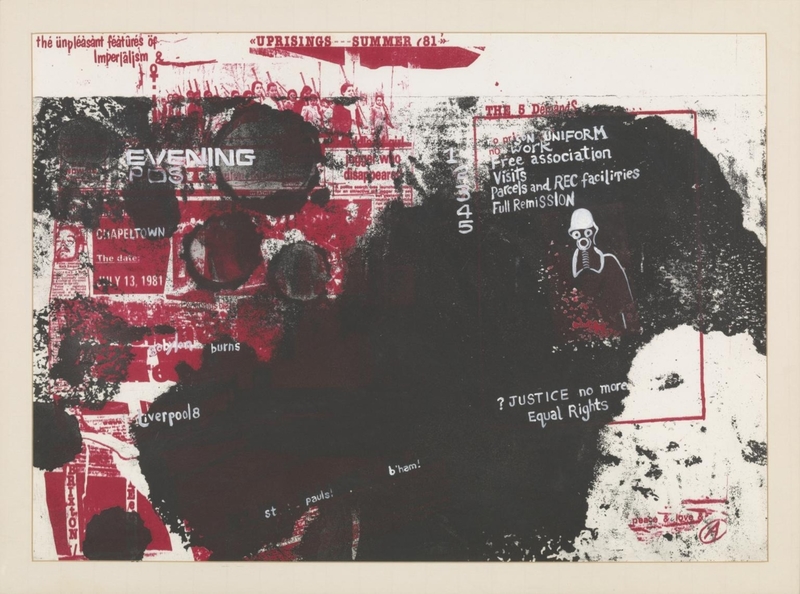

Chila Burman's 'Riot Series': protesting with printmaking 15 April 2024, Jessica Raja-Brown

Chila Burman's 'Riot Series': protesting with printmaking 15 April 2024, Jessica Raja-Brown -

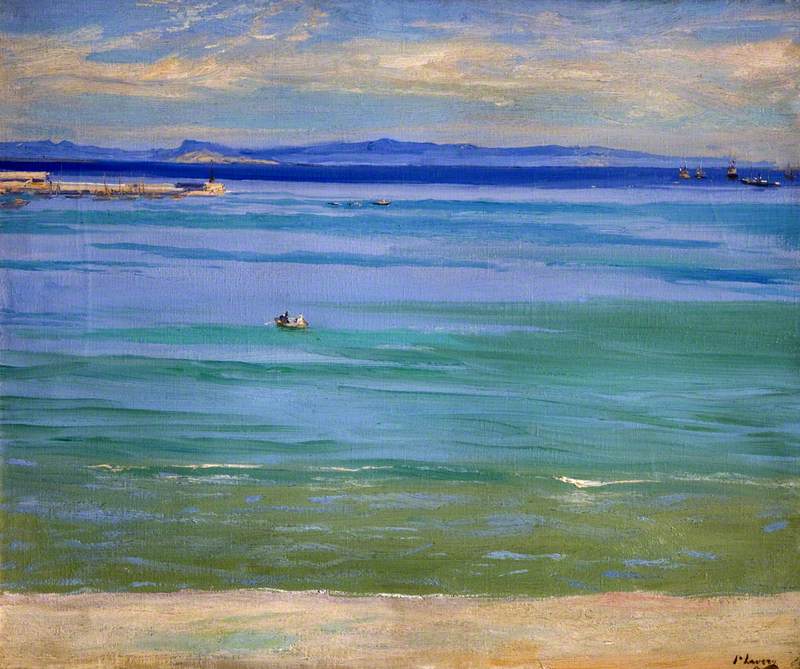

John Lavery's seascapes: the obsession of a restless painter 12 April 2024, Kenneth McConkey

John Lavery's seascapes: the obsession of a restless painter 12 April 2024, Kenneth McConkey -

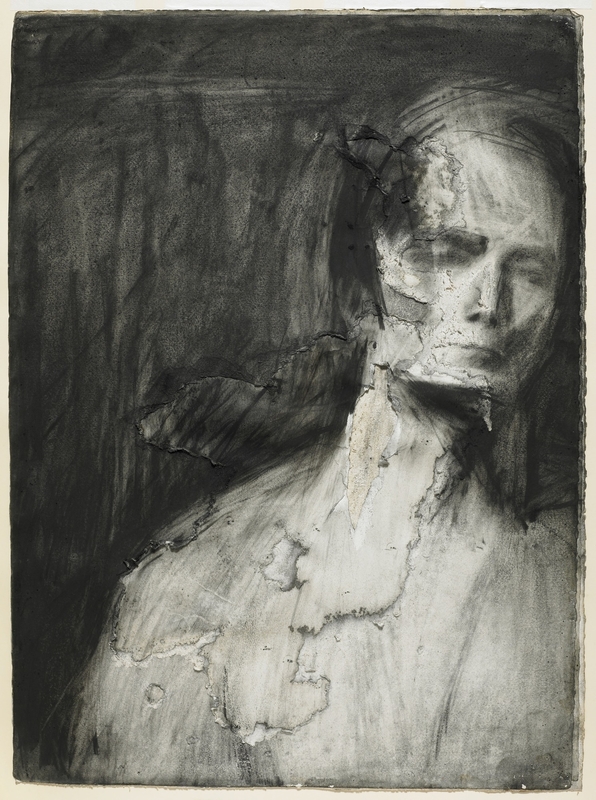

A drawing is a drawing: Frank Auerbach's charcoal heads 10 April 2024, Edward Richards

A drawing is a drawing: Frank Auerbach's charcoal heads 10 April 2024, Edward Richards -

Leon Kossoff: London, figuration and the Old Masters 9 April 2024, Simon Coates

Leon Kossoff: London, figuration and the Old Masters 9 April 2024, Simon Coates -

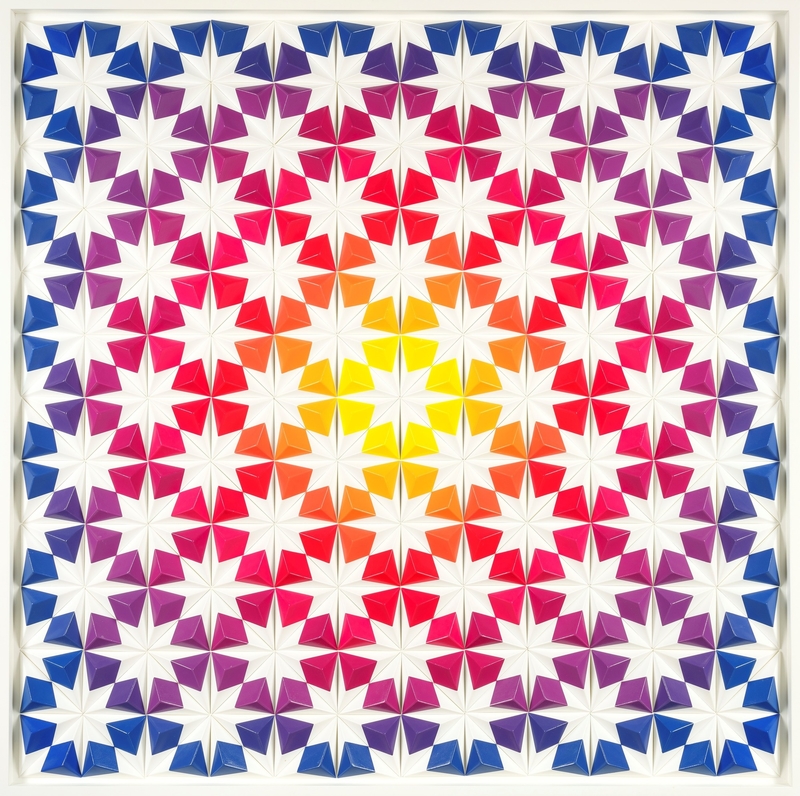

Sacred geometry: Zarah Hussain and Islamic design 2 April 2024, Hattie Spires

Sacred geometry: Zarah Hussain and Islamic design 2 April 2024, Hattie Spires - View all 483

Artwork in focus

View all 267-

Incensed: Alan Kilpatrick's 'Incense Workers' series 8 May 2024, Caleb Carter

Incensed: Alan Kilpatrick's 'Incense Workers' series 8 May 2024, Caleb Carter -

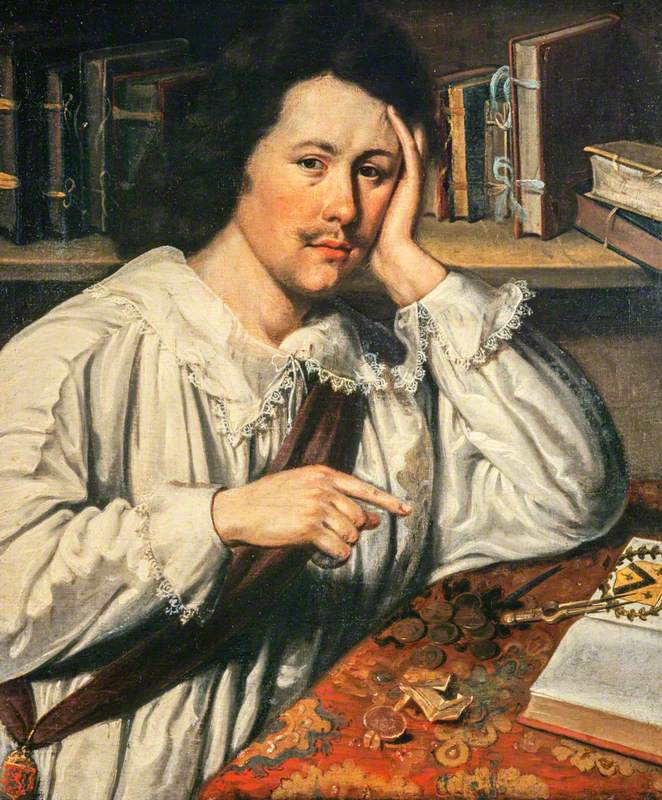

Lord and Lady Belhaven and the mystery of their double portrait 30 April 2024, Cameron Webster

Lord and Lady Belhaven and the mystery of their double portrait 30 April 2024, Cameron Webster -

Shepherdess Walk: Hoxton's hidden mosaics 29 April 2024, George Bartlett and HENI Talks

Shepherdess Walk: Hoxton's hidden mosaics 29 April 2024, George Bartlett and HENI Talks -

Anya Gallaccio's ghostly tree in a Manchester park 11 April 2024, Leanne Green and HENI Talks

Anya Gallaccio's ghostly tree in a Manchester park 11 April 2024, Leanne Green and HENI Talks -

How a statue of Charles I was restored and resurrected in Trafalgar Square 28 March 2024, Timothy Revell and HENI Talks

How a statue of Charles I was restored and resurrected in Trafalgar Square 28 March 2024, Timothy Revell and HENI Talks -

The Apollo Pavilion: Victor Pasmore's optimistic vision for Peterlee 14 March 2024, Stephen Parnell and HENI Talks

The Apollo Pavilion: Victor Pasmore's optimistic vision for Peterlee 14 March 2024, Stephen Parnell and HENI Talks -

Barbara Hepworth's 'Contrapuntal Forms': a utopian vision in Essex 29 February 2024, Irena Posner and HENI Talks

Barbara Hepworth's 'Contrapuntal Forms': a utopian vision in Essex 29 February 2024, Irena Posner and HENI Talks -

Scott of the Antarctic: Kathleen Scott's stoic memorial to her husband 15 February 2024, Ian Christie and HENI Talks

Scott of the Antarctic: Kathleen Scott's stoic memorial to her husband 15 February 2024, Ian Christie and HENI Talks -

Collaboration and devotion: Ben Nicholson's '1932–34 (head)' 13 February 2024, Naomi Polonsky

Collaboration and devotion: Ben Nicholson's '1932–34 (head)' 13 February 2024, Naomi Polonsky -

Ryan Gander's snow sculpture: climate change and cognitive dissonance 1 February 2024, Jeanine Griffin and HENI Talks

Ryan Gander's snow sculpture: climate change and cognitive dissonance 1 February 2024, Jeanine Griffin and HENI Talks - View all 267

News

View all 187-

Autograph x Art UK partnership brings photographs of Britain's diverse communities online 23 April 2024, Art UK

Autograph x Art UK partnership brings photographs of Britain's diverse communities online 23 April 2024, Art UK -

Art UK public sculpture annual report 2023 27 March 2024, Katey Goodwin and Tracy Jenkins

Art UK public sculpture annual report 2023 27 March 2024, Katey Goodwin and Tracy Jenkins -

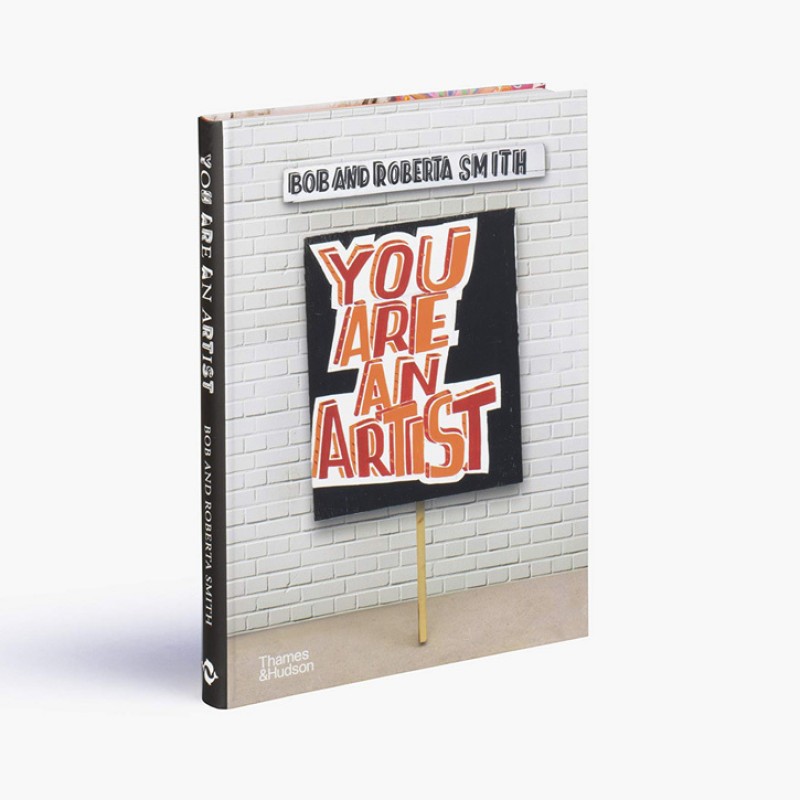

Bob and Roberta Smith RA: art teaches young people to really look at the world 19 March 2024, Gemma Briggs

Bob and Roberta Smith RA: art teaches young people to really look at the world 19 March 2024, Gemma Briggs -

The perfect gifts for mum this Mother's Day 21 February 2024, Barbara Owino

The perfect gifts for mum this Mother's Day 21 February 2024, Barbara Owino -

Announcing our new murals digitisation and engagement programme 6 February 2024, Katey Goodwin

Announcing our new murals digitisation and engagement programme 6 February 2024, Katey Goodwin -

Stoke-on-Trent public art survey – share your views 29 November 2023, Katey Goodwin

Stoke-on-Trent public art survey – share your views 29 November 2023, Katey Goodwin -

The best art gifts for Christmas 17 November 2023, Art UK

The best art gifts for Christmas 17 November 2023, Art UK -

Christmas at the new improved Art UK Shop 27 October 2023, Art UK

Christmas at the new improved Art UK Shop 27 October 2023, Art UK -

Celebrating 2,000 stories and 2,000 Curations on Art UK 24 October 2023, Art UK

Celebrating 2,000 stories and 2,000 Curations on Art UK 24 October 2023, Art UK -

Introducing the new Art UK Shop 13 October 2023, Art UK

Introducing the new Art UK Shop 13 October 2023, Art UK - View all 187

Artist interview

View all 76-

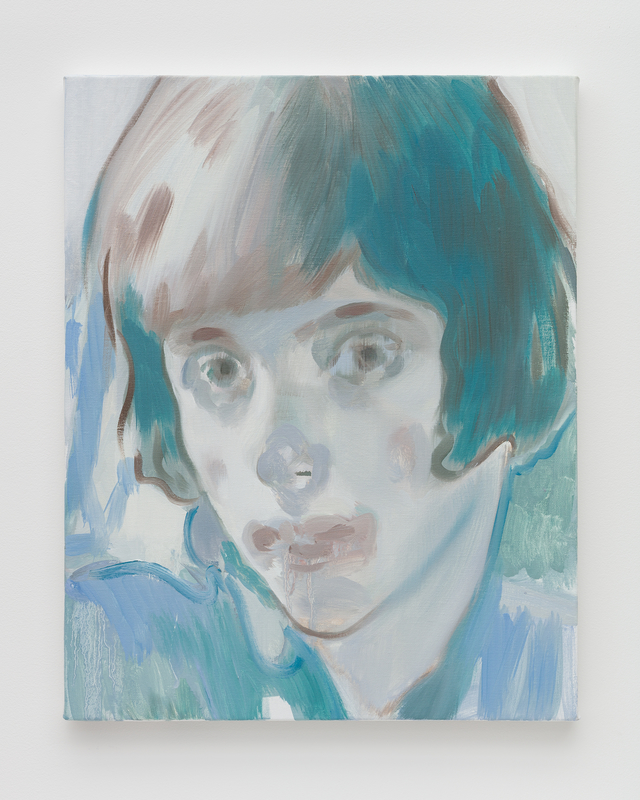

Seven questions with Kaye Donachie 28 March 2024, Chloë Ashby

Seven questions with Kaye Donachie 28 March 2024, Chloë Ashby -

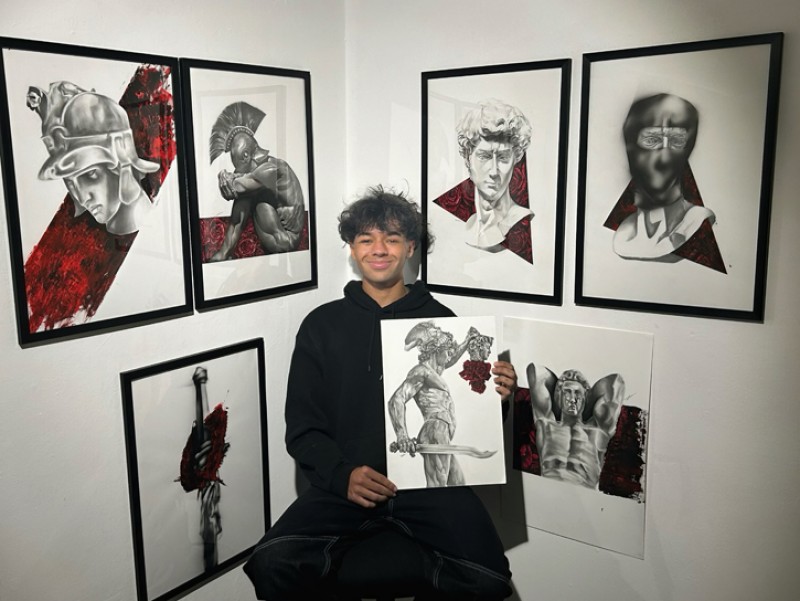

Layton Hylton: drawing inspiration from Stoke-on-Trent's public sculpture 21 March 2024, Katey Goodwin

Layton Hylton: drawing inspiration from Stoke-on-Trent's public sculpture 21 March 2024, Katey Goodwin -

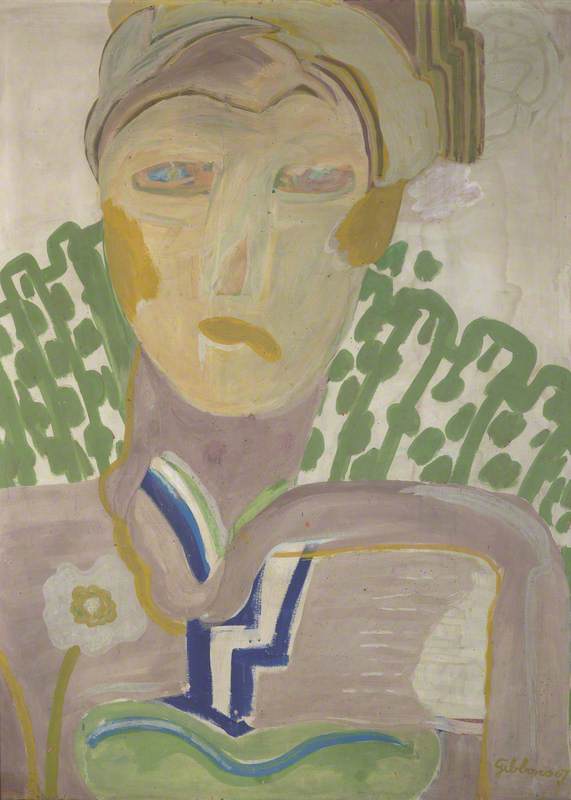

Carole Gibbons: a life in painting 23 November 2023, Calum Sutherland

Carole Gibbons: a life in painting 23 November 2023, Calum Sutherland -

Lionel Playford at Hartlepool Art Gallery: nature and creativity 12 May 2023, Angela Thomas

Lionel Playford at Hartlepool Art Gallery: nature and creativity 12 May 2023, Angela Thomas -

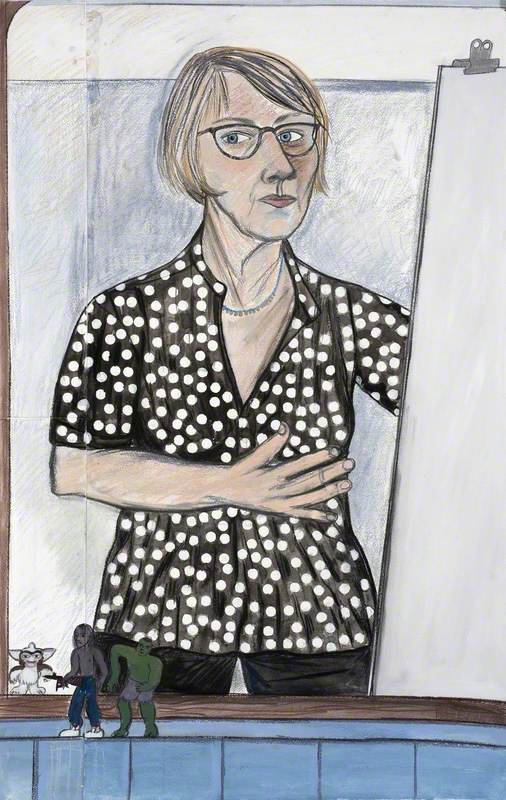

Jane Joseph: A Life Drawn 24 March 2023, Melissa Baksh

Jane Joseph: A Life Drawn 24 March 2023, Melissa Baksh -

Seven questions with Chila Kumari Singh Burman 16 March 2023, Rohini Kejriwal

Seven questions with Chila Kumari Singh Burman 16 March 2023, Rohini Kejriwal -

Seven questions with Paul Scott 20 December 2022, Gemma Briggs

Seven questions with Paul Scott 20 December 2022, Gemma Briggs -

Seven questions with Tschabalala Self 28 November 2022, Julia DeFabo

Seven questions with Tschabalala Self 28 November 2022, Julia DeFabo -

Seven questions with Eileen Cooper 8 November 2022, Lydia Figes

Seven questions with Eileen Cooper 8 November 2022, Lydia Figes -

Seven questions with Anthony Luvera 7 October 2022, Gemma Briggs

Seven questions with Anthony Luvera 7 October 2022, Gemma Briggs - View all 76

Art Matters podcast

View all 68-

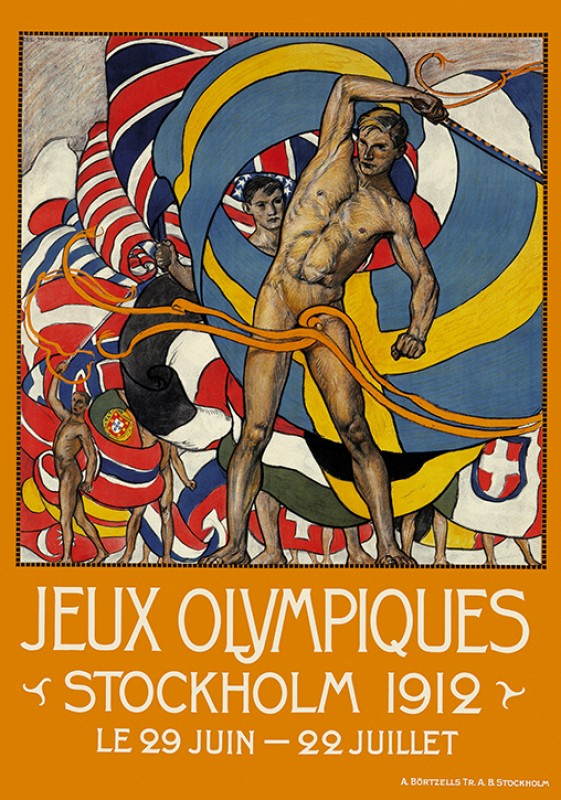

Art Matters podcast: art at the Olympics 27 October 2020, Ferren Gipson

Art Matters podcast: art at the Olympics 27 October 2020, Ferren Gipson -

Art Matters podcast: the art of love 13 October 2020, Ferren Gipson

Art Matters podcast: the art of love 13 October 2020, Ferren Gipson -

Art Matters podcast: the artistry behind maps 29 September 2020, Ferren Gipson

Art Matters podcast: the artistry behind maps 29 September 2020, Ferren Gipson -

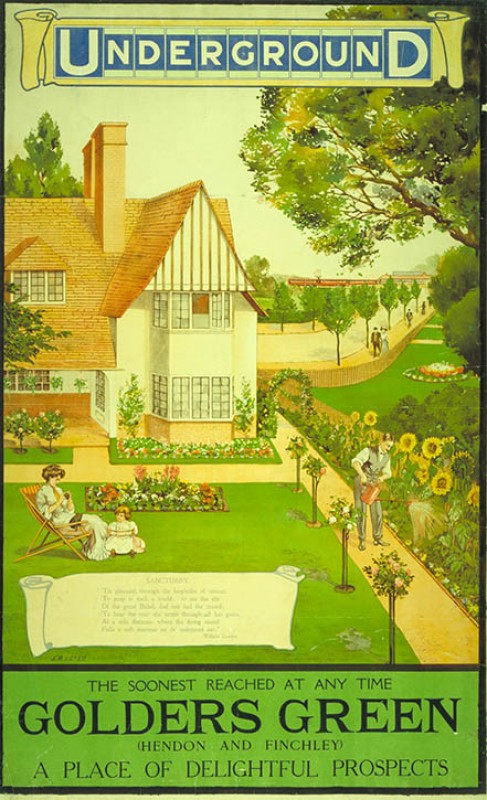

Art Matters podcast: poster designs for the London Underground 15 September 2020, Ferren Gipson

Art Matters podcast: poster designs for the London Underground 15 September 2020, Ferren Gipson -

Art Matters podcast: art good enough to eat 1 September 2020, Ferren Gipson

Art Matters podcast: art good enough to eat 1 September 2020, Ferren Gipson -

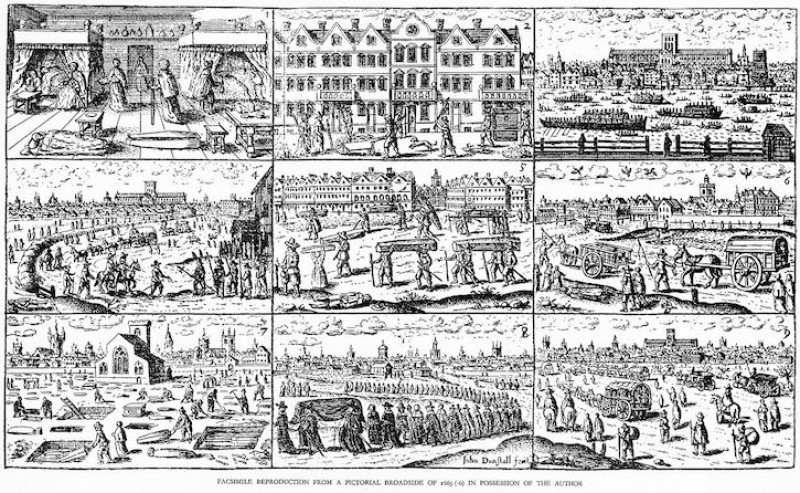

Art Matters podcast: 1666 – a year of plague, fire and war, told through art 18 August 2020, Ferren Gipson

Art Matters podcast: 1666 – a year of plague, fire and war, told through art 18 August 2020, Ferren Gipson -

Art Matters podcast: psychoanalysing art 4 August 2020, Ferren Gipson

Art Matters podcast: psychoanalysing art 4 August 2020, Ferren Gipson -

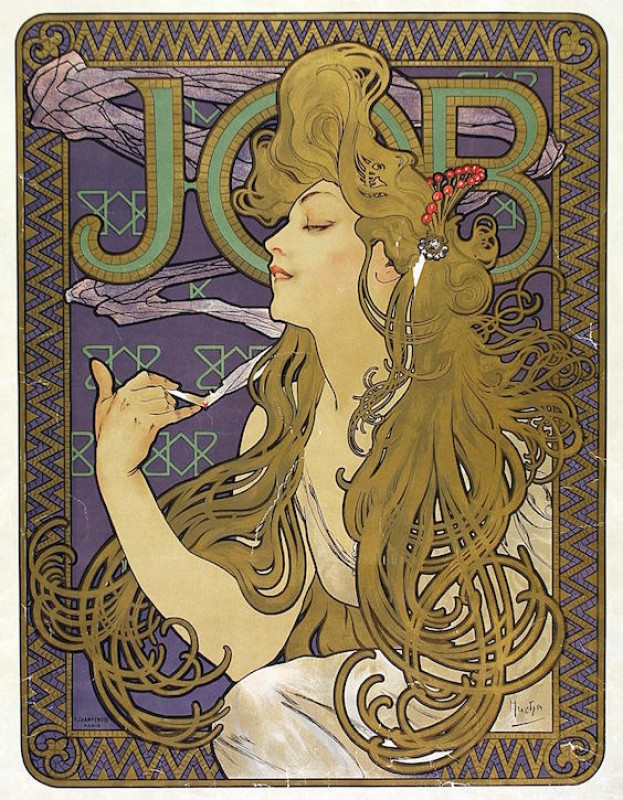

Art Matters podcast: art and advertising 21 July 2020, Ferren Gipson

Art Matters podcast: art and advertising 21 July 2020, Ferren Gipson -

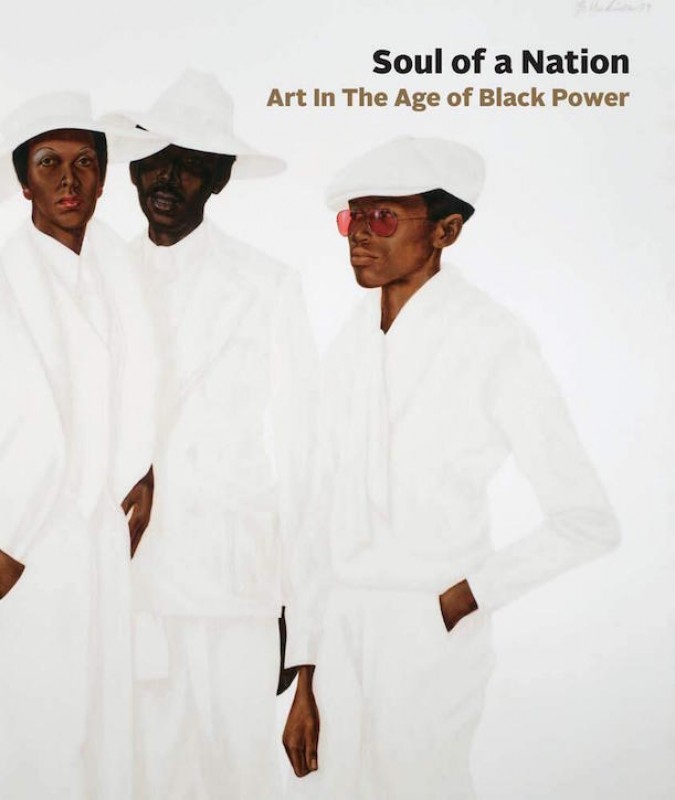

Art Matters podcast: soul of a nation 16 June 2020, Ferren Gipson

Art Matters podcast: soul of a nation 16 June 2020, Ferren Gipson -

Art Matters podcast: the art of twentieth-century British railway posters 2 June 2020, Ferren Gipson

Art Matters podcast: the art of twentieth-century British railway posters 2 June 2020, Ferren Gipson - View all 68

Exhibition in focus

View all 191-

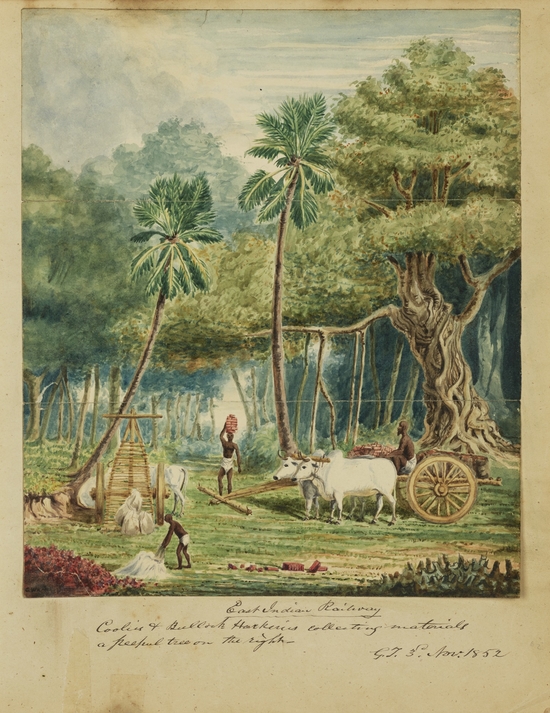

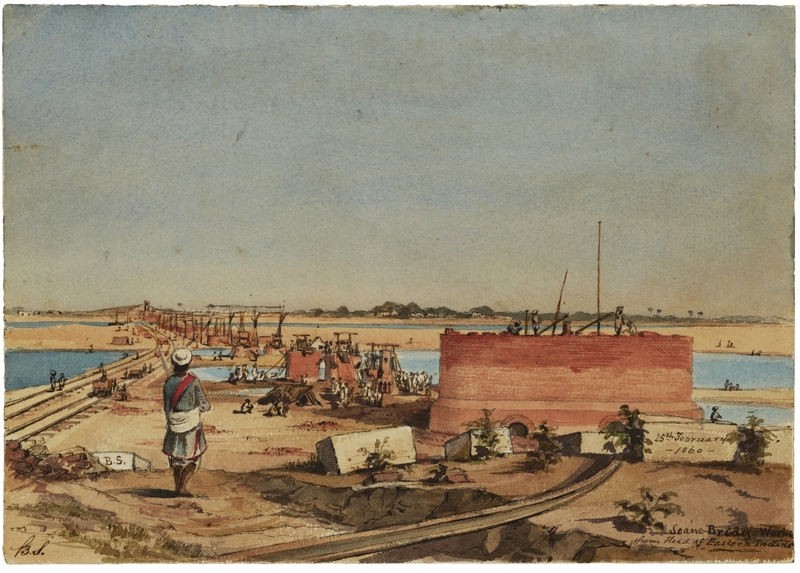

The Empire on paper: visualising British India 29 April 2024, Surya Bowyer

The Empire on paper: visualising British India 29 April 2024, Surya Bowyer -

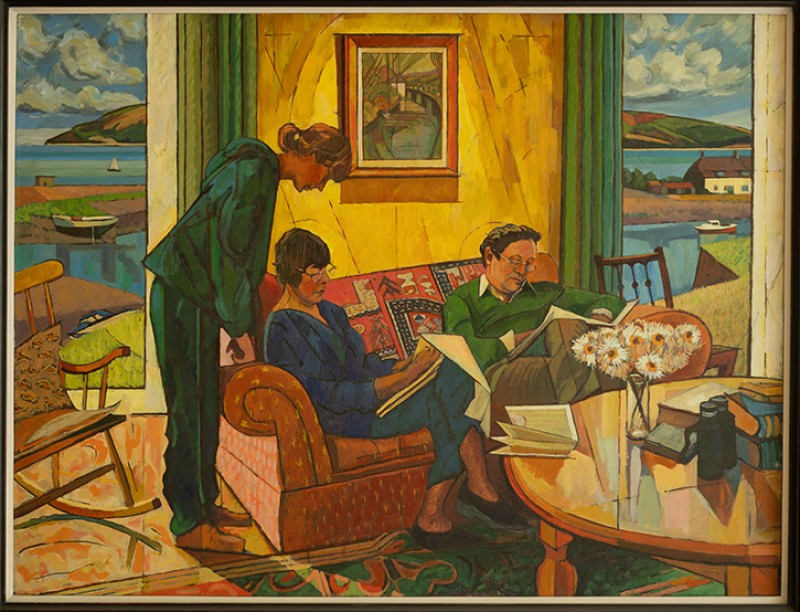

Keeping contemporary: 25 years of the Wakelin Award 25 April 2024, Peter Wakelin

Keeping contemporary: 25 years of the Wakelin Award 25 April 2024, Peter Wakelin -

A sense of place: diversifying landscape painting at Dulwich Picture Gallery 20 February 2024, Jennifer Scott

A sense of place: diversifying landscape painting at Dulwich Picture Gallery 20 February 2024, Jennifer Scott -

Five must-see works in 'Alexander Hollweg: Journeys in Art' 28 November 2023, Sarah Cox

Five must-see works in 'Alexander Hollweg: Journeys in Art' 28 November 2023, Sarah Cox -

Rebecca Salter at Gainsborough's House 21 November 2023, Gill Hedley

Rebecca Salter at Gainsborough's House 21 November 2023, Gill Hedley -

Opulent origins: 200 years of fine art at Bristol Museums 10 November 2023, Emma Meehan

Opulent origins: 200 years of fine art at Bristol Museums 10 November 2023, Emma Meehan -

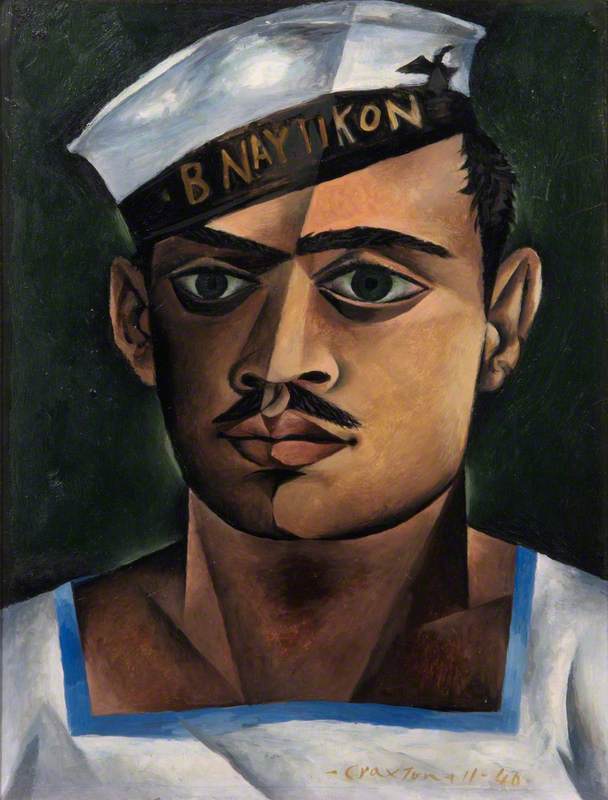

John Craxton: a modern odyssey 2 November 2023, Pallant House Gallery

John Craxton: a modern odyssey 2 November 2023, Pallant House Gallery -

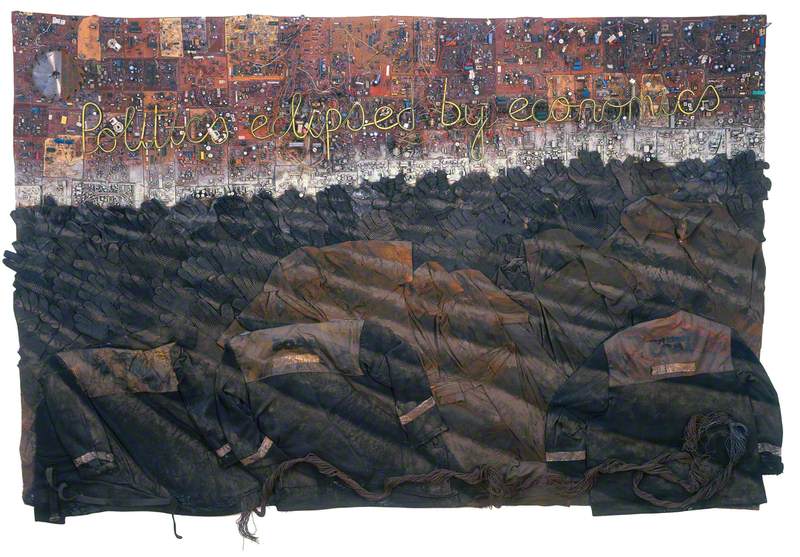

Morley Gallery's 'embodied': resistance and rest 19 October 2023, Melissa Baksh

Morley Gallery's 'embodied': resistance and rest 19 October 2023, Melissa Baksh -

Colin Middleton at the Ulster Museum: understanding Belfast's mid-century modernist 19 October 2023, Dickon Hall

Colin Middleton at the Ulster Museum: understanding Belfast's mid-century modernist 19 October 2023, Dickon Hall - View all 191

Collection in focus

View all 103-

Race, rights and representation: Autograph's photography collection 18 April 2024, Autograph ABP

Race, rights and representation: Autograph's photography collection 18 April 2024, Autograph ABP -

Introducing The Embroiderers' Guild collection 9 April 2024, Anne Haigh

Introducing The Embroiderers' Guild collection 9 April 2024, Anne Haigh -

William Moorcroft, potter extraordinaire: inspiring a new generation at Moorcroft 5 April 2024, Catherine Gage

William Moorcroft, potter extraordinaire: inspiring a new generation at Moorcroft 5 April 2024, Catherine Gage -

Erchyll: depictions of bodies under duress in the collection of STORIEL, Bangor 27 March 2024, David Cleary

Erchyll: depictions of bodies under duress in the collection of STORIEL, Bangor 27 March 2024, David Cleary -

An introduction to The David and Indrė Roberts Collection 4 March 2024, Sander Hansen

An introduction to The David and Indrė Roberts Collection 4 March 2024, Sander Hansen -

Mayoral portraits at Belfast City Hall: an evolving vision of a changing city 18 January 2024, Bronagh Lawson

Mayoral portraits at Belfast City Hall: an evolving vision of a changing city 18 January 2024, Bronagh Lawson -

Belfast Health and Social Care Trust: a collection with a distinctive vision 11 January 2024, Conor McCafferty

Belfast Health and Social Care Trust: a collection with a distinctive vision 11 January 2024, Conor McCafferty -

A Bloomsbury interior in Belfast: Duncan Grant and his circle in the Ulster Museum 24 November 2023, Eva Isherwood-Wallace

A Bloomsbury interior in Belfast: Duncan Grant and his circle in the Ulster Museum 24 November 2023, Eva Isherwood-Wallace -

How Manchester Contemporary helps Manchester Art Gallery acquire new works 8 November 2023, Natasha Howes

How Manchester Contemporary helps Manchester Art Gallery acquire new works 8 November 2023, Natasha Howes - View all 103

Being...

View all 28-

Being... Caitlin McNeill, Island Culture Officer for CHARTS 21 March 2023, Caitlin McNeill

Being... Caitlin McNeill, Island Culture Officer for CHARTS 21 March 2023, Caitlin McNeill -

Being... Dez Quarréll, co-founder and artist-in-residence at Mythstories 22 July 2022, Dez Quarréll

Being... Dez Quarréll, co-founder and artist-in-residence at Mythstories 22 July 2022, Dez Quarréll -

Being... Mark Noble, artist and Ambassador for Outside In 26 January 2022, Mark Noble

Being... Mark Noble, artist and Ambassador for Outside In 26 January 2022, Mark Noble -

Being... Vivian Ross-Smith, Programme Coordinator at Gaada, Shetland 22 October 2021, Vivian Ross-Smith

Being... Vivian Ross-Smith, Programme Coordinator at Gaada, Shetland 22 October 2021, Vivian Ross-Smith -

Being... Jim Ewen, Technician at Project Ability, Glasgow 27 September 2021, Jim Ewen

Being... Jim Ewen, Technician at Project Ability, Glasgow 27 September 2021, Jim Ewen -

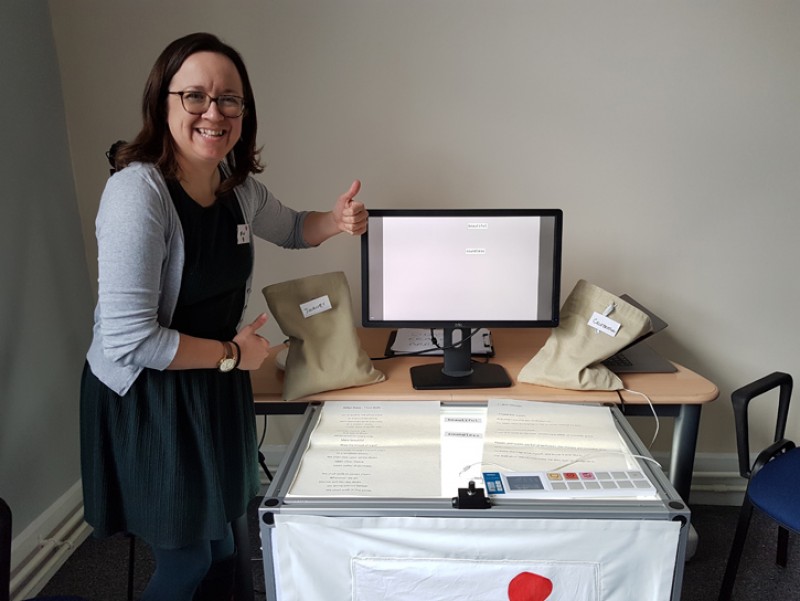

Being... Dr Abi Roper, Speech and Language Technologist at City, University of London 24 August 2021, Abi Roper

Being... Dr Abi Roper, Speech and Language Technologist at City, University of London 24 August 2021, Abi Roper -

Being... Wells Fray-Smith, Assistant Curator: Special Projects, Whitechapel Gallery 28 June 2021, Wells Fray-Smith

Being... Wells Fray-Smith, Assistant Curator: Special Projects, Whitechapel Gallery 28 June 2021, Wells Fray-Smith -

Being... Claire Craig, Curator at Travelling Gallery 25 May 2021, Claire Craig

Being... Claire Craig, Curator at Travelling Gallery 25 May 2021, Claire Craig -

Being... Louise Dunning and Abi Spinks, Curators of Fine and Decorative Art, Nottingham City Museums 5 January 2021, Louise Dunning and Abi Spinks

Being... Louise Dunning and Abi Spinks, Curators of Fine and Decorative Art, Nottingham City Museums 5 January 2021, Louise Dunning and Abi Spinks -

Being... Francis Raeymaekers, Curator at Marchmont House 4 January 2021, Francis Raeymaekers

Being... Francis Raeymaekers, Curator at Marchmont House 4 January 2021, Francis Raeymaekers - View all 28

Art UK Home School

View all 22-

Art UK Home School: The Great Big Art Exhibition 18 February 2021, Shane Strachan

Art UK Home School: The Great Big Art Exhibition 18 February 2021, Shane Strachan -

Art UK Home School: create a softer world with Brendan Jamison 15 December 2020, Shane Strachan

Art UK Home School: create a softer world with Brendan Jamison 15 December 2020, Shane Strachan -

Art UK Home School: draw five inspirational objects with Bob and Roberta Smith 8 December 2020, Selina Levinson Drake

Art UK Home School: draw five inspirational objects with Bob and Roberta Smith 8 December 2020, Selina Levinson Drake -

Art UK Home School: create your own logo 16 November 2020, Jo Taylor

Art UK Home School: create your own logo 16 November 2020, Jo Taylor -

Art UK Home School: telling stories through sculpture with Hazel Reeves 24 September 2020, Hazel Reeves

Art UK Home School: telling stories through sculpture with Hazel Reeves 24 September 2020, Hazel Reeves -

Art UK Home School: make your own colour sculpture 27 August 2020, Ania Bas

Art UK Home School: make your own colour sculpture 27 August 2020, Ania Bas -

Art UK Home School: create a wire hybrid creature 13 August 2020, Fiona Campbell

Art UK Home School: create a wire hybrid creature 13 August 2020, Fiona Campbell -

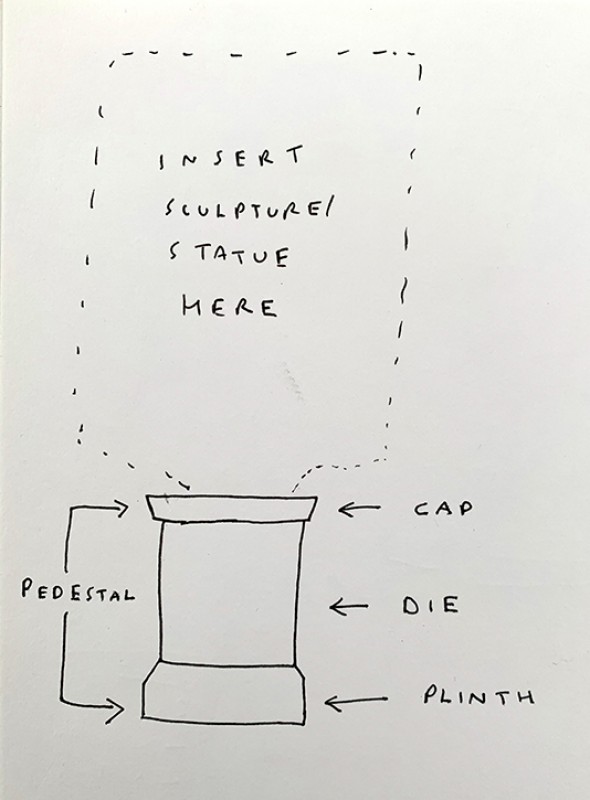

Art UK Home School: who's on the pedestal? 30 July 2020, Sam Ayre

Art UK Home School: who's on the pedestal? 30 July 2020, Sam Ayre -

Art UK Home School: take flight with a winged sculpture! 16 July 2020, Shane Strachan

Art UK Home School: take flight with a winged sculpture! 16 July 2020, Shane Strachan -

Art UK Home School: write a summer haiku 2 July 2020, Shane Strachan

Art UK Home School: write a summer haiku 2 July 2020, Shane Strachan - View all 22

Conservation in focus

View all 17-

The restoration of a 'Lady' at Ordsall Hall in Salford 7 December 2023, Peter Ogilvie

The restoration of a 'Lady' at Ordsall Hall in Salford 7 December 2023, Peter Ogilvie -

Welcome home, 'The Welcome'! The journey of one man and his dog 30 June 2023, Amy Brunn

Welcome home, 'The Welcome'! The journey of one man and his dog 30 June 2023, Amy Brunn -

Art conservation: the final touches 29 June 2023, Simon Gillespie

Art conservation: the final touches 29 June 2023, Simon Gillespie -

Sympathetic retouching 22 June 2023, Simon Gillespie

Sympathetic retouching 22 June 2023, Simon Gillespie -

Overpaint: the audacity of past restorers! 15 June 2023, Simon Gillespie

Overpaint: the audacity of past restorers! 15 June 2023, Simon Gillespie -

Varnish removal 8 June 2023, Simon Gillespie

Varnish removal 8 June 2023, Simon Gillespie -

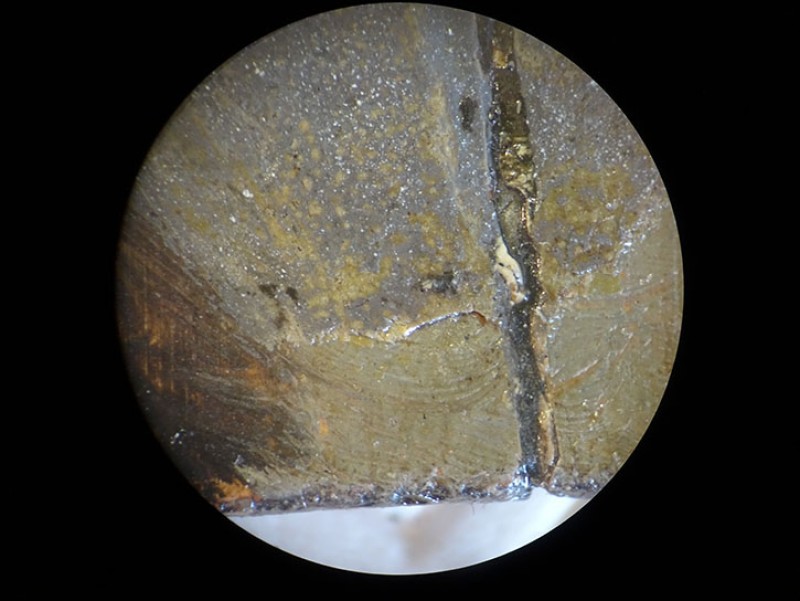

Works on canvas: mending tears and flattening undulations 1 June 2023, Simon Gillespie

Works on canvas: mending tears and flattening undulations 1 June 2023, Simon Gillespie -

Treating artworks: works on panel 25 May 2023, Simon Gillespie

Treating artworks: works on panel 25 May 2023, Simon Gillespie -

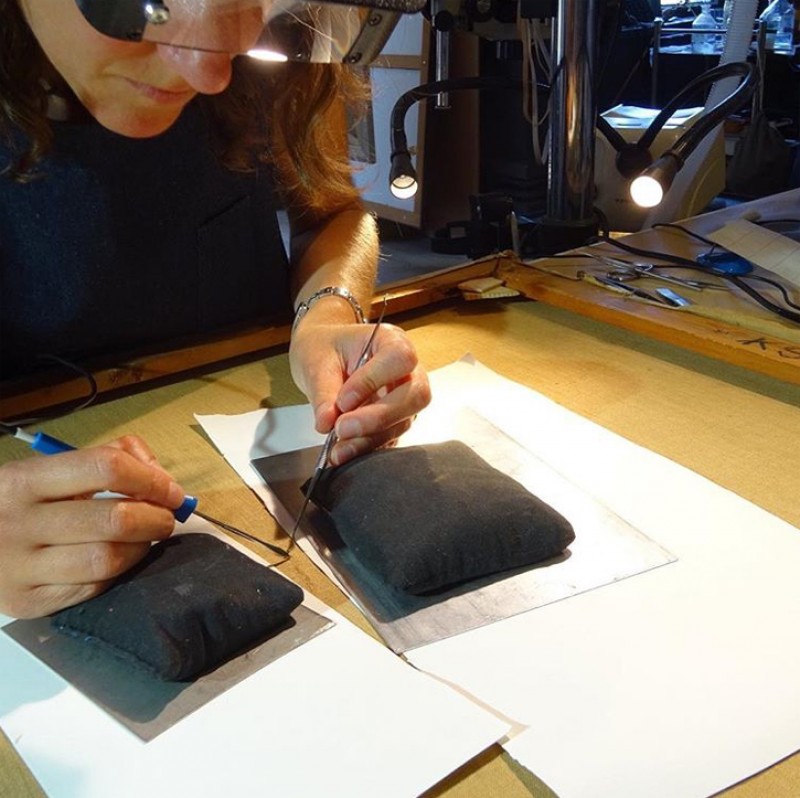

Paint analysis for art conservation 18 May 2023, Simon Gillespie

Paint analysis for art conservation 18 May 2023, Simon Gillespie -

Using x-ray and infrared images 11 May 2023, Simon Gillespie

Using x-ray and infrared images 11 May 2023, Simon Gillespie - View all 17